Introduction

A Two year road

Introduction

A Two year road

For the past year and a half I’ve had a dull ache in the front of my head.

Not a migraine, but a persistent pressure that starts above my eyes and radiates outward to my temples. On good days I can almost forget it is there. On bad ones, the pressure is so strong I sense that I am living my life in the third person, watching my body stumble its way through the world. In April 2015, I learned that I have neurological Lyme disease. The result of a poppy seed sized tick that embedded itself just east of my belly button as I walked through a field in the hills of upstate New York. I got the bite in the summer of 2013, a month after I graduated college. I remember feeling exhausted and having shooting pains through the side of my head. But I was also running a Kickstarter campaign for this project – to pay to make a film about student debt – and as my doctor and I agreed, I was probably just stressed out.

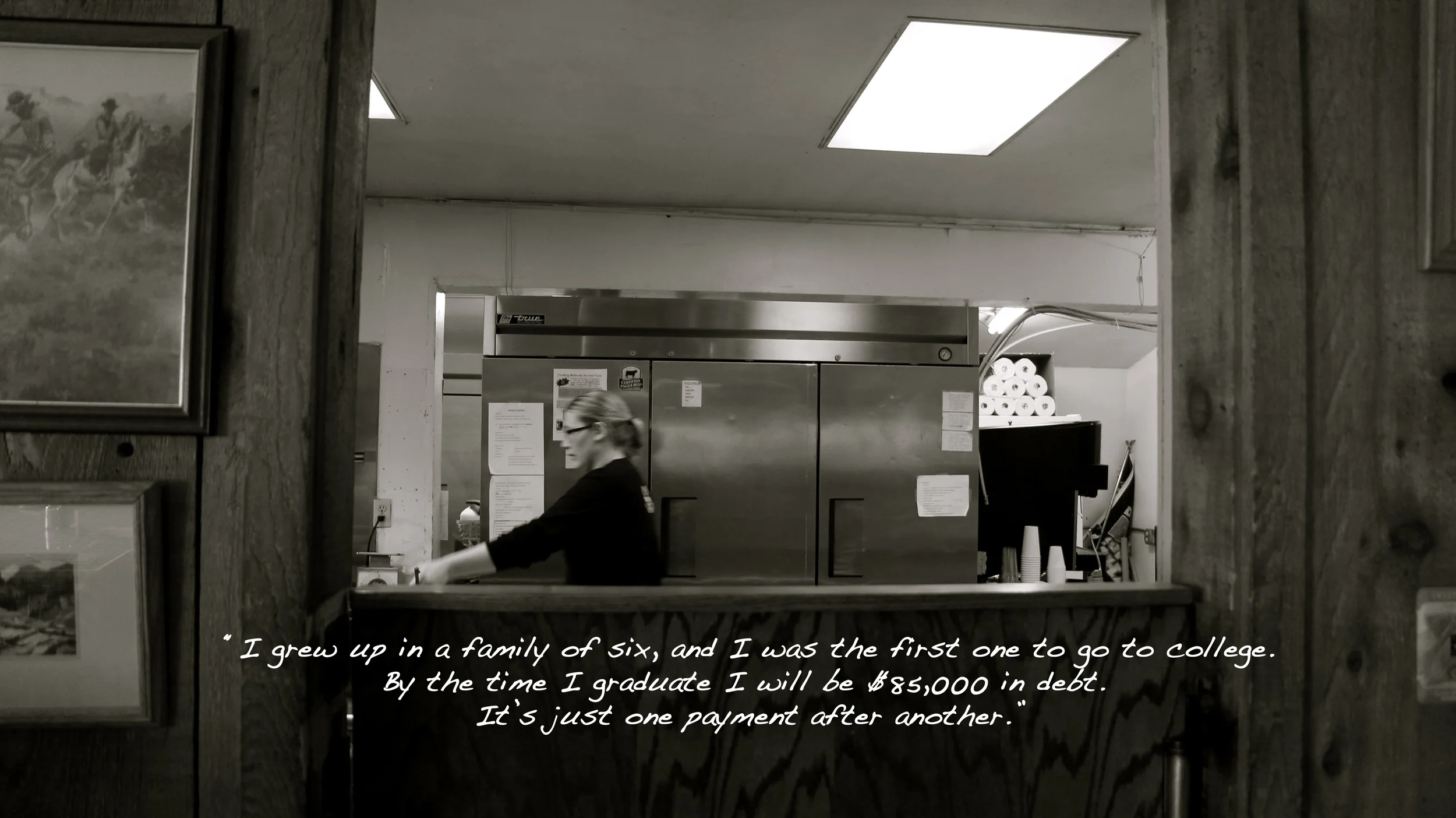

As a precaution I was tested for Lyme disease, but as 45% of Lyme tests do, it came back negative. What came back positive was my Kickstarter. I had $26,500 to make a film about student debt and unemployment so I did my best to ignore my symptoms. I used the money to buy camera equipment, gas, and food, as my good friend and I spent seven months driving over 18,000 miles across the country. We met hundreds of people and conducted over 70 interviews. The focus of our conversations was the student debt crisis, but the stories we heard went far beyond economics. I was stunned by the profound effects student loan debt had on peoples’ lives. Some had defaulted on their debt or had their wages garnished; others had become depressed and considered suicide. A system they had believed was built for their betterment was now holding hostage their chance to a normal life. Most said that they felt trapped, that by pursuing an education they had lost their freedom.

When I returned home in the summer of 2014, so did my symptoms of Lyme. My headaches got worse, until sometime in the winter they just stopped going away. From the time of the bite it took two years, and countless misdiagnoses to finally have a doctor tell me what was wrong.

The diagnosis of Chronic Lyme Disease is heavily disputed in the medical community. It’s understood that if you treat the disease right away you have a high chance of success. But if you’re like me, and it’s misdiagnosed or ignored for two years, many doctors don’t understand the best ways to heal. I was forced to look outside of the medical establishment to find someone willing to treat me. Insurance companies refused to pay my medical bills. Three times a week, I had antibiotics pumped intravenously into my arm. Each treatment cost hundreds of dollars. I was told I was doing the right thing, and yet I felt stuck paying for something I desperately needed but couldn’t afford. Had it not been for my family’s help, I would have been homeless and bankrupt at 24 years old.

I tell you all this because having Chronic Lyme Disease was the first time in my life that I realized how easy it is to be unlucky. Throughout my trip, I often heard pundits’ say that with more “personal responsibility” graduates wouldn’t be so buried in their debt. This perception seems embedded in the American mythos, and I was surprised to find that I wasn’t immune to it. Having never experienced much misfortune myself, I sometimes succumbed to thinking that what had happened to these graduates could never happen to me. Having Chronic Lyme Disease changed that; I was forced to understand how it feels to watch yourself lose control.

After seven months of treatment, my symptoms have gradually subsided. I can focus for longer periods of time; I can work again. For this, I have my family to thank. Many people are not so fortunate – when their luck runs out they’re left on their own. So perhaps the debt story is more of an American story: If you have the support, you have the opportunity to excel. Without that support, you have little room for bad luck.

Chapter 1

Welcome to Marco's

Chapter 1

Welcome to Marco's

I met Tim on a cold grey day in the parking lot of a strip mall south of Edmond, Oklahoma.

It was the middle of February and the snow had warmed into a blanket of slush. The outskirts of Edmond were flat, a stretching expanse of fast food chains and big box stores. It looked like the rest of America that I had driven through – uniform in its corporate identity. Tim worked at Marco’s pizza. When I met him, he was in the middle of a 6-hour shift, running inside to grab some boxes before heading out on another delivery. He owned an old Chevy sedan, whose timing belt squealed loudly whenever he put the car in reverse. He used the car for work, and paid for the gas with the money from his tips. He was a big man with a good sense of humor, and as he returned to his car he held open a massive tear in the crotch of his jeans.

“Coldest day in three years”, he said, “and this is what happens to my pants”.

He placed the boxes in the backseat and settled into the car. The pizza was for a man named Eric, who had ordered a large pepperoni to the BMW showroom.

Tim’s family moved to Edmond, Oklahoma when he was ten years old. His dad was transferred from an oil refinery in Texas to another just south of Oklahoma City. The work paid well and the family was comfortably middle-class. As Tim described it, he wasn’t spoiled, but he had almost everything he wanted. In the mid 90’s, however, Mobil, in the process of merging with Exxon, began laying off its workers, turning to contract labor that didn’t require them to pay benefits. Tim’s dad, two-and-a-half years from earning his pension, was given a pink slip and no retirement. The CEO at the time, Lee Raymond, eventually retired with a 400 million dollar compensation package.

His father found various jobs around Oklahoma; at one point working as a long-distance trucker. He was a 52-year-old man though, and he never found anything that paid nearly the wage that his job at Mobil did. After a few years, the family declared bankruptcy. Tim told me, “The bankruptcy took everything”. A hard-earned college fund for the children was completely drained. All of Tim’s siblings were forced to take out student loans. His mother was disappointed, but she still believed college was a necessary step toward a successful life.

Tim was raised blue-collar, but he left high school with a love for the arts. He was a talented actor and hoped to pursue this in college. Moving to Los Angeles was his dream, but his financial situation seemed to make it impossible. UCLA actually extended an offer for him to come audition for their theatre program. The audition was in Chicago though, and it was two weeks away. Tim didn’t have the money to make the trip. He shook his head as he told me this; “Story of my life, never had the money for anything.”

He ended up bouncing around various state schools throughout the region, eventually ending up at 2-year community college to receive an Associates degree in film. Film became his new passion, and again he set his sights on LA. He took a tour at Chatman University, but never heard back. Not having much of a portfolio, his choices came down to Columbia College Hollywood, or a new school that had just opened, American Intercontinental University. AIU had a housing plan, so Tim enrolled for the fall semester. He went to LA on his own. He was 21, he knew no one, but he felt that this was where he needed to be – in the center of things, near to his passions. Not having any money to live or pay for school, he consulted the financial aid office at AIU. They signed him up for a student loan of $32,215 from Sallie Mae. The loan came with a 13.2% compounding interest rate that started growing the second he signed for it. It seemed like enough money to survive for two years. He was told that everyone had loans, that it was the good debt to take – and so he accepted it. He told me that at the time he had no idea how interest rates worked.

(Tim acting in a local and national commercial.)

Tim told me that he did well for himself in LA. He was cast in a national commercial, and he drew interest from many of the faculty at AIU, helping them rework their screenplays to pitch in Hollywood. His professors, who were UCLA grads, told him he was a talented writer, and he began to focus on writing screenplays. After graduation he seemed set to work in the mailroom of a leading talent agency, but at the last minute he was told he wasn’t needed, so he ended up moving home to Oklahoma. While home, he was working on a screenplay with a professor, but after many drafts and many rejections the possibility of it going anywhere faded. During this time, Tim’s loans came due; Sallie Mae wanted him to pay $700 a month, and before he could grasp the enormity of what he’d signed, the interest began capitalizing. This means that each year the interest earned on his debt was added to his principal balance and charged again at 13.2%. Basically his interest was accruing interest.

Tim graduated in 2006. In 2008 the U.S. economy crashed. Jobs were hard to come by -- not to mention jobs in the Oklahoma film industry. Tim had been working towards a commercial real estate license at the time, but after the crash he figured it was no longer worth it. He had been full time at a real estate office -- the same one his mother worked at -- but she was fired, and he was cut down to part time. The day that this happened his boss looked him in the eye and told him “it’s time to grow up.” Despite this Tim decided not to quit, and on weekends he works as a secretary, occasionally screening calls from debt collectors asking if he’s in the office. “Oh sorry, Tim’s not in right now”, he told me with a smile.

Over the years the interest on his debt grew. He never defaulted, opting instead for forbearance programs, often taking classes to help relieve some of the burden. One of the programs he signed up for soon out of college was a partial pay forbearance program that was presented to him by Sallie Mae. Not being able to afford the $700 a month that they asked for him to pay, Sallie Mae offered an alternative plan. Under this program he could pay $225 a month and they would consider the account in forbearance. What they didn’t tell him was that the interest on his debt was adding around $700 a month to his principle balance. Each month, as he was giving them $225 they were adding close to $500 dollars to his debt. He only found out when Sallie Mae quit the program, and sent him a bill.

His debt is now close to 90,000 dollars, almost three times the principal balance that he initially borrowed. When he showed me his account there was a list of the payments he made each previous month before I met him. He was now paying $700 dollars a month, and every penny of it was interest.

“I've been paying just so I won’t default,” Tim told me. “Just so my credit is not ruined, just so I can eventually one day get a house, and who the hell knows when that will be.”

That night, after his shift at Marco’s pizza, Tim pulled his car into the driveway of a small ranch house in a quiet suburb of Edmond. “It’s bittersweet” he said as he pulled the key from the ignition. “It was good to go out to LA and meet the people that I met, but I regret the decision because of the debt that I got into.” He paused and looked back at me. “But then again I don’t regret it. I regret that I have to pay back all of this money, but it was used for the right thing. It was doing what I wanted to do.”

He opened the door to his car then turned and said, “Now I’m going to scare the hell out of my parents.”

Chapter 2

BIG Numbers

Chapter 2

BIG Numbers

I remember sometime near the end of my senior year in college, I was summoned to the student center to talk about my debt.

I arrived in an auditorium full of Connecticut College’s poorer students. We shuttled through a line, A through M on one side, N through Z on the other. As we went, cheery career counselors handed us a dark envelope emblazoned with our college’s logo. Inside was a sheet of paper with the amount we owed on the past four years of our lives. It even went through the trouble of calculating for us how much money we’d owe every month. Some people opened it right away. Others put their heads down and somberly shuffled into the auditorium, apparently having already been tipped off to their fate. It was early in the morning and our senior spring was almost finished. More than a few students were still high or drunk.

As people shifted in to their seats, their eyes scanned around the room, and they exchanged resigned shrugs as if to say, “Well shit”.

My buddy Neil sat down next to me. We slowly flipped open our folders. I owed $26,500 -- $300 a month for ten years. Neil owed the exact same amount. We tilted our balance sheets toward each other so we could have a look.

“Right on dude!” Neil said, and we gave each other a fist bump.

At that moment, I had $8 in my bank account.

This was how my education to student loan debt began, sitting in an auditorium of hung over people listening to our career counselors as they ran through a PowerPoint about the horrors of default. To be fair to my mother, she tried very hard to get me to understand my situation long before the end of my senior year. I understood that I would have debt, but nothing hammers it home like a balance sheet that says you owe more money than you’ve ever had in your life.

We still had six months before our loans came due. It still seemed far off; my friends and I figured we had plenty of time to find work. But I know someone who left that day with $100,000 hanging over her head. That’s a big number. She signed for that loan when she was 18. Maybe it was different for her, but for me that was the first time anyone at my school had actually explained what it meant to have student loans. I’ll admit that many of us in the auditorium that day failed to take our debt very seriously. I’d say that many of us have learned since. It’s interesting though that all the blame in this crisis usually falls to the students, when the people who knew better didn’t seem all that fazed either.

After accepting my diploma, I returned home, depressed and missing college life. I was forming my adventure across the country, and I decided to do more research on the student loan crisis. What I found was many big numbers. Forty million students were in debt in the United States owing a combined total of 1.2 trillion dollars. The average loan amount was climbing towards $30,000 (for many it was much higher) and over 7 million people had defaulted on their loans. Most interesting though was the numbers that were in decline. Real wages since the 70’s had fallen. Workers with only high school diplomas were making significantly less, and many middle class jobs had been shipped over seas. Before me were many graphs with widening gaps. PEW estimates that college costs increased over 250% since the 1980’s – and that trend is continuing. Yet since 2001, middle class families have seen their median wealth fall by 28%. In the economic crash of 2008, states cut their funding to universities and college tuition rose further. I also found that bankruptcy wasn’t an option for student loan borrowers. For the 7 million in default there was no chance to start over.

Recent graduates have also entered into an economy that relies on unpaid internships. Between 1985 and 2008 the number of graduates completing internships increased from 10% to 80%. Many graduates told me they were either expected to work for free, or have two years of experience for any job that paid. Many had questions about how to get that experience while still paying their bills. As Aaron Smith, the head of the lobbyist group Young Invincible’s told me,

“A young person from a low-income background isn’t doing three unpaid internships in a row, they’re working at Starbucks, so it’s scary to see how that gap that we already have in this country could grow even wider”.

These were the numbers I started my trip with. I looked at the gap between tuition prices and wages, and I decided to hear from the people whose lives filled that void. So many economic issues stay rooted in the numbers. But for me it went beyond that. The debt crisis seemed to undermine the stories I was raised with, about an education meaning opportunity, or hard work equaling success. I wanted to ask people whether they still believed in this American story. I thought by meeting people and having this discussion, by entering their lives, I could learn something more about my own.

Chapter 3

IVORY TOWERS

Chapter 3

IVORY TOWERS

What does it mean to be educated?

This was often the first question I asked in many of my interviews. It was a vague and leading question, but the answers spoke to what an education should do; they provided a roadmap of the ideal. A common theme emerged, that of liberation. I was told that an education was a way to free yourself in the world, to understand how to solve problems, and to be an engaged member of society. Jeff Franklin a Dean at CU Denver told us,

“I really believe the university should produce human beings who add value to the communities to which they belong. So that means preparing people to be productive members of society, to contribute to their local and global communities, and to be active and good citizens. After that, one quickly gets to providing graduates…with the skills and dispositions they need to be happy, productive, healthy, human beings, which includes having a job they want to have, doing work they want to do, and being paid a fair wage for doing it.”

I remember this moment well. We were in a 2nd floor conference room and off to the west were the Rocky Mountains, buried deep in a season of snow. As Jeff Franklin spoke, I started to realize how so many moments on my trip held such deep contrast. These educators believed in their mission, yet their answers seemed less like a reflection of the current system, and more like a measure of how much needed to change. In Denver we interviewed two graduates whose stories were the worst we had heard yet. Professor Franklin’s answer was the ideal, but on the ground, at the base of those mountains, people were still struggling. They fought to pay the bills, and they wondered how the result of their education differed so greatly from his.

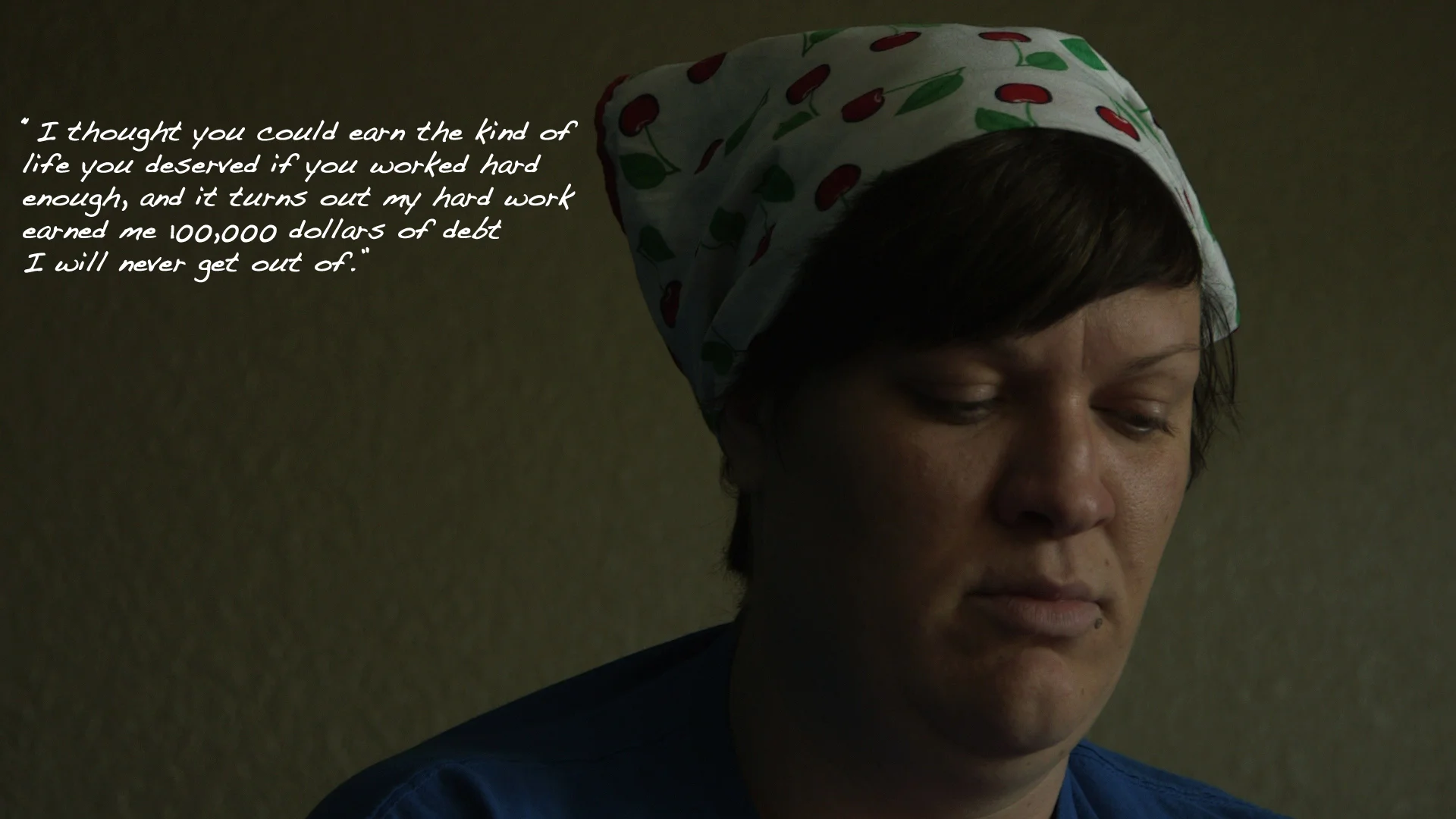

Maybe Bob Wiecowski, California State Senator, put it best when he told us, “There’s value in education, but I strongly believe an education should be a pathway out of poverty, not into it”.

Chapter 4

BAD MATH

Chapter 4

BAD MATH

Nicole Ford arrived at the apartment where I was staying with a stack of folders tucked under her arm.

In the folders were hundreds of pages of loan documents, meticulously labeled and sorted. Sallie Mae, ACS, Nelnet, and Federal (Government), six years of reminders, from four organizations, asking for money she did not have.

Nicole graduated from CU Denver with a degree in Architectural Visualization. After working in the music industry for eight years, she felt she hit a ceiling, and she decided to retrain. The degree she got at CU required extended study rates. 13 of her core classes were charged at $4,200 a class. Combined with the cost of other degree requirements, Nicole left with $120,000 in student loan debt. She graduated in May of 2008. Like many who graduated into the recession she struggled to find work.

During her job search, Nicole discovered that she was taught on a different software than the industry standard. At CU she learned MAYA for 3D visualization, but the jobs she was applying to were asking for proficiency in 3DSMax. In her words, “3DSMax might as well have been Russian”. She tried to take online courses to catch up, but in this time her loans came due, and she owed over $1,000 a month.

In 2006, her junior year at CU, Nicole was injured in a freak accident. She was thrown off a mechanical bull and landed on her back. “It sounds so ridiculous”, she said as she told me the story, but after countless doctors visits and even surgery to remove her tailbone, Nicole has chronic pain and can’t sit for more than 30 minutes at a time. Unfortunately, she graduated with a degree meant for sitting at computers. This, combined with the timing of her graduation, the fact she was trained on the wrong software, and the burden of her monthly loan payments, was enough to cause Nicole to default on her debt.

Nicole’s credit score has been ruined, and the interest on her debt continues to climb. The only good fortune she’s had was qualifying for complete forgiveness of her Federal loans. It was a 3-year process of doctor’s notes and bureaucracy, but finally the Government recognized her condition as permanently disabled. Because the government has regulations on its collection practices, if you become disabled you qualify to have your loans dismissed. But besides the many years it takes to enact this policy, it also comes with some caveats. In Nicole’s case, being disabled means she is unfit for full time work. To the government, this means she can’t make more than the poverty line in Colorado for the next 3 years – a number that comes to around $15,000 a year. If she does, it’s an indication that she has the ability to work, and her loans plus interest would be reinstated immediately. For Nicole that would mean over $50,000 added to the debt that she already owes. What the government won’t consider is that Nicole owes about $80,000 to Sallie Mae, $32,000 to ACS, and $4,000 to Nelnet. Private loan companies aren’t regulated like federal loans, so despite being permanently disabled and only allowed to make $15,000 a year, all three companies are demanding she pay.

The day I met Nicole she had already been called three times. She said she could expect about six calls a day, every day, from different numbers and different people. On her phone she had a list of over 50 blocked numbers from Sallie Mae. She said they call her family, her friends, and previous employers. The day before, Nicole received a message from an ex-girlfriend she hadn’t seen in 10 years. The collection agencies had called, and she was confused as to why.

Nicole offered to call one of the numbers that had called her earlier that morning. A young man from Sallie Mae answered and they talked for 20 minutes about her options. He was excited to offer her a settlement plan. $29,000 it would cost to settle her balance of $76,100.70. They could stretch the settlement over the course of 12 months. If she could pay $2,000 plus interest every month for a year, her debt would be considered paid. In that same year, however, Nicole could only make $15,000 or risk having $50,000 of her federal loans reinstated. Given Nicole’s income, even if every cent she made went to Sallie Mae, she would still be $10,000 short on that settlement deal.

Later, as I scanned some of the papers she had brought, I found another settlement deal that Sallie Mae had offered. They asked for a one-time payment of $52,000 to settle her debt, and they gave her 15 days to make the payment. Etched across the top of this sheet in bold letters were the words “Let us help you get back on track!”.

Sallie Mae holds the keys to Nicole’s future. They can garnish her wages without going to court, they can seize her tax returns or social security, and they can damage her credit so that she never qualifies for a loan again in her life. It seems counterintuitive though. In their thirst to make her pay immediately, they’ve stripped her of the possibility to pay in the future. Unable to find work she defaulted on her loans, they responded by increasing her interest rates, adding on collection fees, and ballooning her principle balance. Now she needs an even better job to begin paying them back, but they also attacked her credit rating, so any employer that runs her credit score will know she’s hit hard times. Many I spoke with told me they weren’t hired because of their credit check. It seems that if this wasn’t the case, Sallie Mae might have less loans in default.

Sallie Mae is a publicly traded corporation with strong ties to Wall Street banks. They must maintain high profit margins to keep their shareholders happy, and their business practices reflect their thirst for a healthy bottom line. The truth is that “back on track” isn’t good business; it doesn’t lead to large profits.

Before she left, as she gathered her folders, I said, “I’m sorry, you must feel totally trapped”.

“Yeah”, she said, “it affects my entire life.”

Chapter 5

Who's Sallie?

Chapter 5

Who's Sallie?

Sallie Mae was created as a government subsidized entity (GSE), a middleman on government guaranteed student loans, much like Fanny Mae and Freddy Mac.

As the Clinton administration started talk of lending directly to students, however, Sally Mae began the push to privatize. In 2004 they became fully private, yet in 2005 87% of their portfolio was still government guaranteed student loans. This means that at that time they were lending with no risk. If students defaulted taxpayers picked up the tab. Being privatized, however, opened them up to start giving private credit loans, which they began to originate. Giving private loans to students was still a high-risk business though, so Sally Mae spearheaded a lobbying effort that resulted in the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 2005, signed into law by President George W. Bush.

This act opened the doors for private lenders to have enormous powers when collecting their debt. It stripped students of any consumer protections and allowed banks to lend money without the worry of losing it to bankruptcy. Private credit loans exploded between 2005 and 2007. In this time the percentage of loans Sallie Mae gave to students without any involvement of an academic institution, increased from 40% to 70%. Riding the subprime mortgage wave, Sally Mae began giving out subprime loans. Although these loans were not federally guaranteed, they offered the benefit of unregulated interest rates. Between the interest and fees that they saddled borrowers with it is estimated some students were paying as much as 28% in annual interest on their loans. When the market crashed, in order to hide the damaging effects of their subprime lending, Sallie Mae aggressively funneled borrows who were in danger of default into forbearance programs, hiding the potential of these unflattering numbers to end up in their accounting books. Basically they pushed the defaults a year or two down the road. It was highly illegal, and became one of the numerous class action lawsuits they have faced since being privatized. Other lawsuits have been filed naming “racist, discriminatory, predatory lending”, and the giving out of loans that top executives have called “predictably uncollectible”.

Between 1995 and 2005 Sallie Mae’s stock returned over 1,900%. Albert Lord, CEO during Sallie’s push to privatize, made 225 million dollars between 1999 and 2004. In 2008, as the government bailed out Wall Street, they allowed Sally Mae to sell back their loans to the Department of Education, and the company’s profits increased to 324 million dollars that year. In 2010 President Obama finally introduced legislation to allow the Department of Education to lend directly to students. This ended the flow of federally guaranteed money for Sallie Mae’s use, although the year before it ended Sallie Mae still had 154.1 billion dollars of federal money on its books.

In talking to graduates about their experiences with Sallie Mae, I started to wonder whether they secretly encouraged default, or at least were willfully negligent in their desire to keep students from it. So many of the settlement deals, or programs they offered, were completely impossible given the borrowers finances. A situation Sallie Mae must have completely understood. What I found, is that as Sallie Mae started to privatize in the 90’s they began to buy up companies that make loans, guaranty loans, and collect on loans. In the late nineties they bought GRC – the General Revenue Corporation, and USA Funds. At the time these were two of the largest collections agencies in the country. In 2014 Sallie Mae split, and created a company called Navient. Navient is now one of the largest private debt servicing companies in the United States. When a student defaults these servicing companies like Navient, can add a 25% collection fee to their debt, and can collect up to 28% commission on any debt that is paid. The students are left paying this bill. What this means is that Sallie Mae only makes money once on a balance that is current. On loans in default they have the opportunity to profit three times. In their eyes, although default may mean higher risk, it can also mean a much higher reward.

In 2005 fee based revenue accounted for 30% of Sallie Mae’s business. Debt Collection accounted for 18%. These numbers have only increased. Sallie Mae has also managed their risk in another way. Almost half of their private credit loans are co-signed by a parent. When many students default, their families default with them.

Sallie Mae isn’t the only one profiting off the student loan system in this country. Wells Fargo, JP Morgan Chase, Citibank, and Bank of America, all have growing student-lending programs. They are buoyed by the Department of Education (DOE) which gives out 1.4 billion dollars a year to collection agencies to service federal debt. Citibank and JP Morgan Chase own two of the largest agencies that the DOE uses. Sallie Mae profits from this as well, taking money from the government to collect on debts. In 2012, 335 million dollars from the DOE went to 23 private collection agencies. The left over money – from the 1.4 billion paid by the DOE – was often outsourced to these same private collectors.

The Federal Government isn’t much better. They stand to make 184 billion dollars from student lending over the next 10 years. Their recovery rate on defaulted Stafford Loans is between 104 --109%. To put that into perspective, the recovery rate on credit card debt is around 15%. What the government offers is a fixed interest rate, and the opportunity for an Income Based Repayment Plan. Despite their windfall profits, they are by far the best option for loans that students have. That doesn’t mean there aren’t horror stories of students dealing with the Department of Education, it just means that at the least government loans are forced to be regulated.

So it’s clear that student lending is big business for both the Federal Government and Wall Street. Yet with 1.2 trillion dollars in outstanding student loan debt, the debt crisis has begun to look like the housing crisis. It has been called the next bubble that will burst. The difference is that Wall Street found a loophole that they didn’t with the housing market; student loans can never be declared in bankruptcy --it’s a type of debt that can’t be foreclosed on. Borrowers have been stripped of their protections, and the result is that Wall Street gets to determine who wins. If Sallie Mae wanted to help Nicole Ford, they could. They have the power to provide an avenue for people like Nicole to rejoin society. But she makes them more money when she’s in default, and so they offer her deals they know she can never pay, trying to squeeze out every dollar as she falls further into crisis.

Chapter 6

Fast Food Saviors

Chapter 6

Fast Food Saviors

Deanna Dunn, Director, Engineering Co-op and Placement. Followed by Bill Johnson

When I interviewed Billy he spoke for 30 minutes before I even asked a question.

He had a story to tell and finally the ear of someone who would listen. It happened often throughout my trip. As those I interviewed became more comfortable with me, their words poured out completely unprompted. In America, we live and die by our dreams of prosperity. We are buoyed by stories of wealth and success. We believe in the power of the individual, the bootstraps, the hard work, and the payout on those dirty jobs. We carry these stories as our national burden. For if they serve to inspire us forward, they also serve the opposite, to chain us to our failures by giving us no one to blame but ourselves. It was easy then as the pathways to the middle class began to erode, to find scapegoats for its decline. Welfare had created a class of takers, black people were lazy, generations were changing, “Millennials” have just been coddled. The result of a country that has so idealized the myth of the “self-made man”, is a country that has protected itself from changing while blinding itself to reality. If the responsibility to progress lies with each one of us individually, then the failing of some to do so is a result of their own inadequacy rather than bad policy or corporate greed. Many people in power understand how to manipulate this dynamic. Systems that fail need radical change. Individuals who fail can be forgotten.

I think it is this type of thinking that allowed the educators I met to nod in unison as they spoke about ownership. It’s what allowed many to say that if only these debtors would work at McDonalds, then they’d have the chance at a normal life. It must be what depressed Billy to the point of considering suicide, after applying to McDonalds twice and getting turned down for being overqualified. So as my subjects opened up, and the words piled on, it was a momentary lifting of an American burden, the shame of being poor.

When people speak about personal responsibility, it only seems to extend in one direction. The kids who take out subprime loans from Sallie Mae are derided for not knowing better, while the adults are applauded for smart business. Students making this decision are 17 or 18 years old. Those overseeing this decision, have children, or own homes, or run companies. Where is the personal responsibility of the Sallie Mae CEO, or the university president, or those in congress that choose to ignore this? Most students I spoke with admitted to their mistakes. They owned their ignorance at the time when they signed. But if blame falls on them, then blame must also fall elsewhere. The system doesn’t work unless everyone is involved, and if the responsibility for this crisis hangs on those at the bottom, then it lies even more with those at the top.

Chapter 7

Costly Ticket

Chapter 7

Costly Ticket

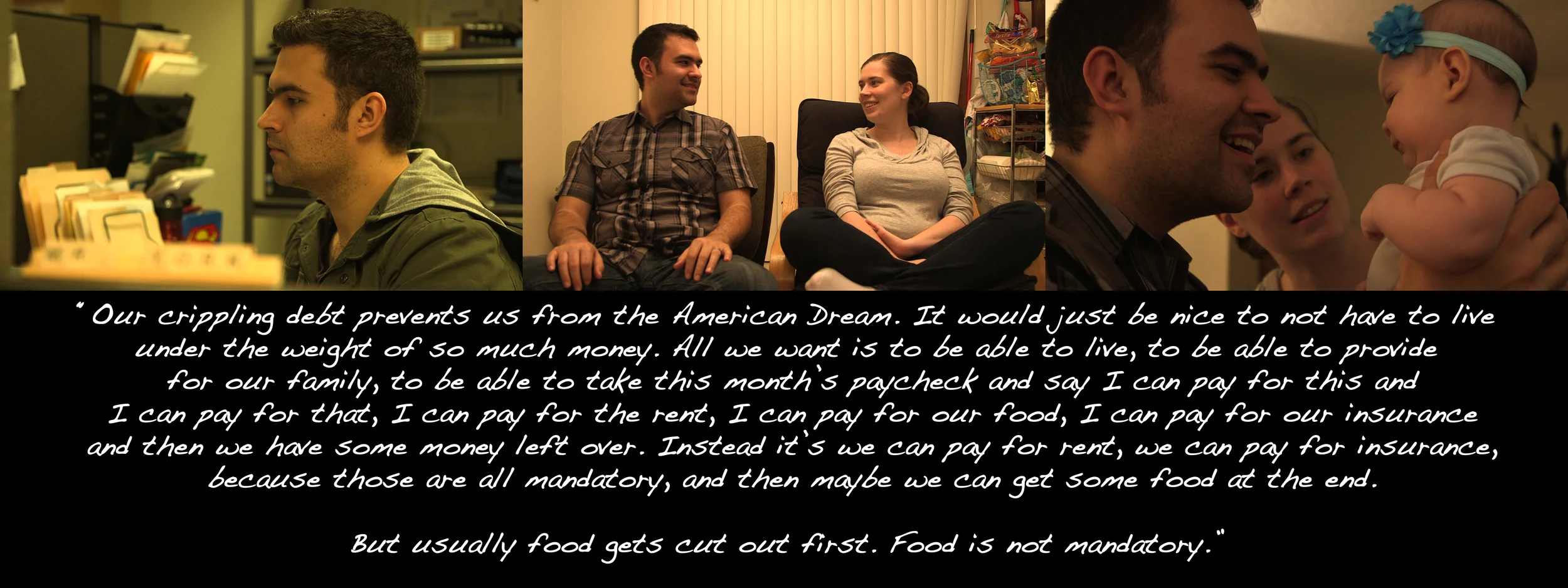

When I rang the doorbell to Taron and Andrea’s apartment building I was met by a 5-year-old boy in a batman cape.

His name was Ethan and he led me up 2 flights of stairs to his family’s apartment. They lived in a 2 bedroom east of the Barclays Center in the heart of Brooklyn, but with two children and a 3rd on the way they were quickly outgrowing the space. On the door to the apartment there was a vision board. It was taped at eye-level and in bold letters on the bottom of the board it read “pay-off student loans”.

Taron and Andrea were born and raised in Brooklyn. Andrea grew up in a housing development and was raised by her grandparents. Taron, the Tompkins projects in Bedstuy, raised by his mother. Their families expected them to attend college. Taron’s nickname was Buddha, and he had an uncle who would sit him down and say, “Buddha, promise me you’ll get out”. He wanted him to go away to school and get a taste of the world. Most importantly, he made him promise to not have a kid before he left.

Although both Taron and Andrea were pushed to go to school, they had no counseling about how they should pay for it. Andrea remembers stuffing a trunk with her belongings, before taking a five-hour Greyhound north to SUNY Morrisville. The bus dropped her at a train station, completely alone, where she managed to get a cab to the campus. Arriving at school was a culture shock. She had two white girls for roommates and was living in the heart of the Finger Lakes – trading cityscapes for farmland and home for something foreign. “I was scared to leave Brooklyn,” she told me, “But I pushed through the fear. I told myself, I don’t know what’s on the other side of this, but I know what’s here and I don’t want to be here”.

Andrea received a two-year associates degree from Morrisville, before transferring to SUNY New Paltz for a degree in business administration. For the past 11 years she’s been a payroll administrator for a non-profit in Brooklyn. She likes her work, and they pay her well enough to have zeroed the balance on her $20,000 of student loans. “It wasn’t easy”, she laughed “but I did it.”

Taron went out of state for college, attending Morris Brown University in Atlanta before the school lost its accreditation for mismanagement of funds. He transferred to Fisk University, and then went on to Case Western in Cleveland to receive a Masters degree in social work. He worked for many years after that, before returning to school for a second Masters degree in education from Baruch College. He now works for the New York City Department of Education at the Brooklyn Collaborative School. The school practices expeditionary learning in the spirit of Outward Bound and Taron’s title is the Restorative Practices Coordinator.

Taron is proud of his current position. But he stressed to me that it has taken him almost 10 years to find a job that compensates for the cost of his education. Being a social worker, the prices of his degrees were much higher than the starting salary that he received – a growing plight for students who work towards the common good. Because of this, Taron went back to school, and 6 months before I met him, he had finished his second masters at Baruch. He now owes $145,000 in student loan debt, and his grace period is over --the bills have come due. As we sat at a table in the living room, Taron knocked his knuckles on the wood and looked up with an apprehensive smile. “I don’t know how many monthly payments I’m going to have to make to pay off $145,000 of student loan debt,” He said, “but tomorrow is Day 1.”

As I talked with Taron and Andrea, their 2-year-old daughter Emmy climbed onto their laps. She grabbed at the microphone, and played with her mother’s necklace, before settling in to listen to the music coming through her large pink headphones. Ethan spent much of the time off singing in his room, but emerged at one point to ask for a cookie. They were happy and well-behaved kids, and as we sat and talked about debt it was clear that Taron and Andrea were toeing the line that all parents walk – providing for their children in the present, while worrying how to pay for their futures.

Taron’s debt has become his family’s debt. This understanding was a burden that he carried. The family was growing; they needed a new car, and a new apartment, if not a house. $145,000 might as well be a mortgage though, and when talking with the banks about getting a home loan, that number had come up. Taron valued his education, but he wished he knew more about debt before he attended college. He remembers arriving at Morris Brown and receiving a bill for his first semester. It was more money then he had ever seen, and as he was rushed through the financial aid office – which had a line out the door – he signed up for whatever loan he could get. “For me, the education around school didn’t come till I was in it”, he told me, “So I resent not being aware, not knowing, which means it’s going to take me longer to get to this ‘Dream’ than I would like to see for this family.”

Despite the cost of being educated, Taron believes that he needed two Masters degrees to open the doors to where he is now. To be taken seriously as a black man, he needed to set himself apart. When I asked Taron about the American Dream, he told me, “Honestly, I have to put race into that equation. The American Dream for a young brown boy is very different from that of my counterpart…I had to get this education, just to sit at the table.”

Taron and Andrea were first generation students. Like many who were the first in their families to attend college, they left school with the burden of debt. Many people say this was the choice that they made. Yet as Andrea and Taron told me, when going to college is the only legitimate path forward, not going isn’t a choice. The student debt system was created to provide greater access to higher education. What Taron reminded me of was that this system is not immune to our countries history of inequality. The debt system provides access with a cost. You have to pay further into it to be taken seriously, and it creates a market where workers need a degree to be hired. In all the towns I drove through, I found graduates serving coffee, or making food, or waiting tables. So if you are poor, and don’t go to college, your chances of finding well paid work are limited. If you are poor, and do go to college, you have to find a way to pay the bill. If you’re like Taron and trying to make it, how high does that bill have to climb? How much do you have to pay to erase your label as a kid from the projects?

Later that day, Taron – also a minister at his church – dressed in a suit and tie and left the apartment to address his congregation. He told me that although it can be hard to live with this debt, he preaches hope to his parish, and as such has to practice it himself. He said you must speak it to believe it, that his family will be okay because they have to.

After he left, we walked with Andrea, Ethan, and Emmy, to a park a few blocks away. As her kids ran for the playground, ducking between posts and swinging on the monkey bars, Andrea looked on. “All that we do is for them to have better opportunities,” she said, pausing to remind Emmy to be careful. “I don’t want Ethan to need a thousand degrees just to sit at the table. I want Ethan to just be good enough with what he comes to the table with.” Later, she would push them both on the swings, one at a time as they screamed in the wind. She told me that Taron’s debt was now her debt. “This is ours now”, she said, “and I don’t want it to hinder what they have. I don’t want them to have to struggle like we do.”

Chapter 8

Theres No Way Like The American Way

Chapter 8

Theres No Way Like The American Way

I met James Feagin at the Red Bull House of Art in downtown Detroit.

He wore Timberland boots, jeans, and a polo shirt that hung down over his waist. “I dressed this way”, he told me, “to see if anyone here will actually talk to me”. The building was filled with young white people in tight jeans and hip jackets, who perused modern art as they drank Red Bull and vodkas. Later on he would tell me, as we drove through a neighborhood of abandoned homes, “Look I got nothing against hipsters, I’m half hipster myself, but hipsters and coffee shops have nothing to do with what’s happening right here.”

James grew up on the East side of Detroit, 5566 Somerset, right near the corner of Outer Drive. He lived in a small brick house that had a big bay window off the front, lined in gold painted trim. As he drove us past it he told us, “This is where my parents embarked on their American Dream, right here in this house”.

When James was a sophomore in high school, his mother moved him further east to the town of Grosse Pointe. The public schools were better, and James got to attend Grosse Pointe South for free. His family was one of the only black families in town. A census at the time reported that the Black population in Grosse Pointe was less then a tenth of one percent. Meanwhile, in the city limits of Detroit, a 5-minute drive away, 87% of the city was black. James remembers his mother setting strict rules about what he could wear when he walked down the street. His father used to come home beaten by the police, his only crime driving on the streets at night.

“I never really understood it until Trayvon Martin,” James told us, “guilty or innocent, he’s dead. And for my mom it was, ‘I don’t have time --and I didn’t raise you and go through all this --to have you dead over some misunderstanding’ – there is no justice in that. There’s no peace for someone going to jail for killing me.”

What James saw growing up was two sides of the American Dream. One was the middle class dream, a modest home, in a good neighborhood, and jobs that put food on the table. The other was the dream of the Grosse Pointe elite, where modern mansions lined the shore of Lake St. Clair as yachts sat waiting in the marinas. His mother had found a way to work him into this second dream, to give him some of the benefits of how the other side lived. Yet driving with James, despite his liberal arts education and his successful career, it seemed that his heart was still with the bricks of that home on Somerset drive.

He drove us through the mansions of Grosse Pointe, eventually heading west back to the city of Detroit. Less than 10 minutes later we were turning on to the street where he grew up. His home still looked the same, but across the way a house was missing its windows, and a block to the west James counted 9 abandoned homes. It was interesting to see that as one dream was dying, 2 miles away the mansions still stood and the yachts were still running.

I went to Detroit because the student loan crisis was compared to the housing crisis, and I wanted to see what it looked like when that bubble had finally burst. Detroit had once been a beacon of economic prosperity, an American symbol of growth and ingenuity. In many ways Detroit fueled the modern depiction of the American Dream. The city produced the automobile, and with it the suburbs and the mobile family that drove the boulevards after work in the cars they helped assemble. But as Detroit helped grow this dream, they were also the beginning victims of its fall. Factory jobs left, plants closed, and a city that had swollen outwards in the shape of a wheel saw its spokes start to loosen as the tire lost air. You can’t hide the amount of homes in Detroit that are falling in on themselves. They populate the areas between the pockets of revitalization, and they spread outward through Detroit’s 139 square miles, encircling the city in a reminder of the costs of urban flight.

Yet although the abandonment in Detroit was undeniable, I was just as surprised by its hubs of activity. There were coffee shops, and good restaurants. It felt much more creative than other cities that I’d been to. I was taken by the graffiti, and the community gardens, and the sense of pride that Detroiters had for the city they were rebuilding. I couldn’t help but start to believe it, when one local told me “the American Dream is alive and well in Detroit”.

James made a point of showing me these places first. He drove me through mid-town, and out towards 8 mile where we rode through a neighborhood of brownstones.

As we drove James said, “People get this narrative that black people don’t take care of their homes, but what did you just see?” He pointed out the window at some young kids raking leaves, “and that’s really the lazy thing about narratives,” he continued, “the people that don’t fit get cast aside”.

James wanted me to see that some people were still living well in Detroit. He also wanted to show me that families are the bedrock of a healthy city – when families stay a community is vibrant, and when they leave that community fails. This neighborhood was a pocket of families that had chosen to stay, but even there, as we drove through the tree lined streets, there were homes with boards across the windows. It seemed a world away from downtown’s revitalization. Where downtown seemed to be coming to life, this neighborhood was hanging on, abandoned by public systems that were failing.

I believe James showed me this to make me realize how complicated this situation was. Despite the coffee shops and the creative ventures that were blossoming downtown, to recover from the costs of economic decline would take holding on to these families. He wanted to show me that if the American Dream was ‘alive and well’ in Detroit, it was a new form of this dream, built from the failing of previous dreams, and at the moment it was still reserved for the few. What Detroit illustrates – and what has been shown across the country – is that when pensions, wages, and jobs are cut, and people are forced to the margins, it creates problems that are extremely difficult to solve. There’s a real cost associated with leaving people behind; you don’t get those lives back. This was something that James made incredibly clear. The opportunity that I was excited by in Detroit was born with a price.

That doesn’t mean this opportunity did not exist though, and if anyone was tuned into this, it was James. He was the co-owner of the Untitled Botega. He and a business partner had started a real estate venture where they bought up an abandoned street block and turned the buildings into an art gallery and community space. The gallery was run by artist and college dropout, Flaco Shalom. It was a type of development that seemed sustainable. It provided opportunities for young locals to stay in Detroit and develop their art into a business. James was quick to understate its impact, but it seemed like the right kind of progress. Started by someone who knew both sides of Detroit --who could build for the future by understanding the lessons of the city he was born in.

The Untitled Botega was a new take on the American Dream. Flaco, the director of the Botega, had left Detroit and enrolled in college, but by dropping out and coming home, he found a backdoor to what he wanted. It was a story that I started to hear elsewhere across the country. As traditional paths to success were becoming less of a sure thing, people were finding their own way forward, away from the systems that were meant to guide them.

As we stood in one of the buildings outside of the Botega, a roofless foundation of cinderblocks covered in paintings of a ballerina, I told James that it seemed like the national narrative was still that you need to go to college and get a job to be successful.

James turned to me and smiled, “We don’t listen much to the national narrative around here,” He said, “or else we wouldn’t be here.” He paused to look around, “We’re standing in an abandoned building, what part of the national narrative is this, am I, is Detroit?”

As I left Detroit I held with me what James said about opportunity being born from cost. The people of Detroit who lost their pensions won’t find relief in the city’s rebuilding, just as many of the people who have defaulted on their loans won’t find ways to recover. Understanding the pain of that loss, in the way that James has been forced to, may be the only way to move forward. Maybe, because of that loss, we have an obligation to change things. Maybe ignoring that pain would be the greatest insult of all.

Chapter 9

GEneration Cupcake and the Star Wars Sheets

Chapter 9

GEneration Cupcake and the Star Wars Sheets

I interviewed Michael Graham, a right-wing radio talk show host, in the office of my friend’s father.

Michael enjoyed yelling directly into the camera, and as we finished the interview we opened the office door to find a floor full of people staring at us with stunned expressions.

At one point in the interview Michael laughed and exclaimed,

“Oh yeah, cause playing XBOX and masturbating in the basement makes you guys ‘Super Brains’!”

This may have been one of the quotes that caught their attention. He was referring to the fact that on college campuses students had begun to receive more “A” letter grades than in generations past. Clearly he did not attribute this phenomenon to the “Millennial” generations budding intellect. Yet despite this, Michael was surprisingly attuned to the student loan crisis.

He told me “A college diploma is worth today what my dads high school diploma was worth for him. Its just getting a ticket punched that shows that you are ready to start being in the world.”

He paused, and then turned to scream into the camera:

I agreed with all of this, and so I was mildly surprised when Michael shifted away from his stance of solidarity. Turning instead to the shortcomings of the so-called “Millennials”.

He ended this all by saying, “No offense”, which must be the world’s worst platitude.

This happened often on my trip. People would speak at length about student loan debt being a horrible burden. Yet in the next breath they would say that more people should work at McDonalds to pay the bills, or that my generation should take ownership like previous generations of harder working people. I heard this often about my generation -- that everyone went home with a trophy or that technology was ruining us. But it’s interesting to me that this criticism comes from the generation of people who are directly responsible for the way we were raised. We didn’t invent this technology, or make up these rules. Much of this was put in place for us, and I think it came from a place of love. I wonder now, when the criticism from older generations becomes strangely vitriolic, what happened to that love, that desire for our generation to have the chance to be anyone or to be protected from the harms of the world?

There is no doubt that technology has had a massive impact on my generation. It changed the way we communicate, and yes it gave us the selfie. Yet we didn’t invent narcissism, nor do we have any power to stop it. Technology just gave us a new platform to project our adolescence to the world. As musician Levi Weaver told me, “Thank god I didn’t have twitter when I was 15”.

So what does set us apart? If the “Millennial” grouping is taken seriously, then 35 year olds are being generalized with 15 year olds. Perhaps the only thing that ties this group together – the one thing that makes us unique – is the high cost of college, and the burden of debt we take for a degree we believed we needed. “Millennials” are graduating into an economy that is recovering from the largest economic downturn since the Great Depression. Wages are lower, median family income is lower, yet rent, healthcare, food and loans cost more. This is the new reality that is affecting everyone but the richest Americans. “Millennials” have simply graduated into this reality. More “Millennials” live at home, because they’re not paid enough not to.

Near the border of Tennessee, I received an email from a middle-aged white guy named Gary. I know this because he started the email with, “I’m a 57 year old white male.”

It went on to read, “I hope that you're not just another wannabe filmmaker whining and complaining about the state of things without any idea of the reason much less a solution for the problems this country's millennial generation currently faces. And just interviewing a bunch of clueless young graduates, MTV style whining, about not being able to get a job, is about as useful as a bunch of kindergartners doing a feel good circle-hug after receiving participation trophies for losing a game. Misery loves company but it ain't very productive.”

Gary reached out to me unsolicited to offer this opinion. But he wasn’t alone. What was it that made people so mad at my generation? The lawyer in $160,000 of debt just wanted a job. The 24 year old with $85,000 of debt who worked three jobs while getting a masters, wasn’t lazy. This was their life. Where I think the anger might come from is that younger people have begun to point out the promises that they feel were broken. This can be threatening, because if we were raised into broken promises, it means that those above us both built them and broke them -- that they may be responsible for why things are failing.

Yet this type of criticism, which is sweeping and generalized, often serves a stronger purpose. In many ways, the dismissal of Millennials’ concerns is a protection of the status quo. There are many people profiting from these systems who are resistant to change. It always seems easier to dismiss activists, than to entertain the reality that comes with their concern. So perhaps the anger from above comes as those below step out from the prescribed. Perhaps the anger comes for many because they’re scared to think there was another way, afraid to admit that they may have got it wrong.

Also, it seems like if there was a time to encourage someone it might just be kindergarten…but then again, I’m a sucker for hugs.

Chapter 10

THE Emails

Chapter 10

THE Emails

Below is a story that I constructed from the many emails that I received on this trip.

Every word was written by students in debt, and pulled from an actual email that was sent to me.

Dear Winslow,

I’m not usually one to place blame on anyone other than myself for my woes, and I suppose in a way my current situation is my own fault in that I was more enamored with the idea of having a college degree --the first in my family to do so --than interested in the realism of the job market. I graduated from school in ’09 after the crash. While things have been tough since, this was probably the worst, most uncertain time of the recession. I remember my college actually cancelled the annual career fair for graduating seniors due to the lack of employers planning to attend. I currently hold a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from Colorado State University and a Juris Doctor from Drake University Law School. I am also unemployed, have no assets, and have approximately $160,000.00 and growing in unsecured student loan debt.

Growing up, pursuing higher education was always a foregone conclusion for me. The importance of a college degree had been stressed to me for as far back as I can remember.

But even though my parents couldn’t afford to help me with tuition or living expenses, they made too much for me to qualify for financial aid. I had to find another way to pay for college. The problem was that, though everyone expected me to continue my education, I am at a loss to think of a soul that provided any guidance with regard to the financial element. In essence, I found myself as a high school senior, with an acceptance letter, a tuition bill and absolutely no idea what to do next. The only piece of advice that I received regarding my tuition bill that was even remotely helpful was, “pay it.”

I decided to hold a job while I was in school but I couldn’t even generate enough income to cover rent and groceries let alone pay tuition rates that went up exponentially for each semester I was enrolled.

I graduated with Honors yet I was unable to find an entry-level position because there were too many graduates and not enough jobs to go around. What I was told is that I don't have experience, and I was supposed to get that experience with unpaid internships when I was working to pay for college.

Between May of 2010 and February 2011, I applied for over 200 jobs in both the private and public sectors. The jobs I was applying for ranged from corporate counsel positions to barista positions at Starbucks and I made it a point to follow up with every company/agency I applied to. Out of over 200 emails sent and phone calls made, one was returned. I currently have a position at Goodwill that pays me slightly more than minimum wage. After student loans, taxes, rent, utilities, insurance and transportation, I often have to borrow money from friends and family to buy groceries. I’m only a couple weeks away from losing my apartment and my car. For me the recession of 2008 never ended. I will never be able to buy a house, make investments, go on vacation, send my children to college or do anything besides live paycheck to paycheck.

I wouldn’t mind accepting that the “American Dream” is broken, if I didn’t have to listen to rich people on TV talk about “Lazy Americans”, when I would happily take a 2nd job if anyone was hiring. Then I might be able to over-come this debt. But, my parents busted their asses for 36 years, and their jobs were sent overseas. So “lazy” might as well be the way. “Hard work” gets you bankruptcy, if you’re lucky.

And yet I can’t declare bankruptcy like my parents did, because that’s not allowed for student loan debt. So I just fall further behind, as I make the minimum payments, and try to put away $100 here or $100 there.

The worst are the two loan companies Sallie Mae and ACS. Sallie Mae has been so cut throat and unforgiving. They refused to work with me even though they know the position that I am in. They call several times a day, they call my friends and family to ask where I am, and they have ruined my credit. The government has no laws surrounding private student loan companies and what they can or cannot do.

So I will likely lose everything..... but the debt remains. I will have to start over when I find work and I imagine it is going to be even more difficult. There is so much more I have to say. I cannot even begin to express the anger and resentment I feel towards "the system" that lets things like this happen. I am an honest, hardworking person and there is no help for my family or me. My health has suffered from the stress and my marriage has suffered as well. I no longer think long term. I have learned to live day by day. It is the most insurmountable weight I have ever carried in my entire life and the biggest burden that my wife and I have.

Thanks for hearing me out. It is hard when you are told all of your life that you need a college degree to succeed, and by the time you accomplish that you are screwed. You get put into such a hole that you couldn't possibly dig yourself out and the interest just keeps on adding up. The great irony is that if I had pursued a career in the arts and failed spectacularly, I would still be about $160,000.00 richer right now. Hell, if I had borrowed $160,000.00 to put in a pile and set on fire, or any other purpose aside from trying to better myself through education, I would still be in a better place due to the potential viability of bankruptcy. In short, student loans have made getting an education the biggest regret of my life.

Thank you for reading.

Chapter 11

Honest Abe and the sunglasses Shoot

Chapter 11

Honest Abe and the sunglasses Shoot

Somewhere in the massive expanse of the Great Plains, as we drove from Wichita to Denver, I started to realize that my trip was built on contradictions.

As we made our way west, the interviews took on a different tone. We started meeting people with oppressive amounts of student loans. At the center of all of this was me. I was a common string linking all of these people, and I began to cringe at how that string unraveled behind me. There were the shots of me in my sunglasses sitting in front of the Lincoln Memorial. There was the trailer I edited of me being epic near sunsets, and the shots of me as I explored barren fields, and coal trains, and gassed up my car in fake Raybans. I slowly came to hate this, both on the trip and after, and I began to take myself completely out of everything. It wasn’t until over a year after I returned that someone I was working with was smart enough to tell me, “that’s part of the story, that speaks to a lot”.

Two years later, this is what I’m left with. It’s not a feature length film. I still wish that one day it might be, but for now this is it, this website that I hope in some way can bring life to these stories. What I was given was the chance to learn by doing, to own something that was completely mine, and I was forced to be the one that drove it forward. Over the last two years I was given the space to make mistakes. I was freed to explore. This trip gave me the chance to practice. I now have other opportunities. Opportunities that might actually pay me, and despite this project not being exactly what I thought it would, it’s the very thing that led me there.

Looking back on the footage of this trip, there are things I’m deeply proud of, and things I’d love to bury in a hole far away from human eyes. That to me seems like the lesson in all of this. I think we all have things we want to say, and it takes a long time, longer than college, to learn how to say them. I was given the chance to engage in that process. I think that’s the important part of getting to a place that you want to be. I think we all need that time, and I think what my trip showed me more than anything, was how few of us get it.

Chapter 12

Opting out

Chapter 12

Opting out

In Western Colorado, where the desert plains rise up to meet the snowcapped mountains, there is an old mining town called Paonia.

Before town, as you drive from the south, there is a snaking dirt road, rutted and muddy, that leads up to the top of the plateau and looks out over the valley. It was here that we met two men, Dev and Eric, one with a Masters and a PhD, and the other a college drop out, who had both come to believe in the un-schooling movement.

Dev lived off the grid in a house made of recycled materials. The walls were a mix of stucco, plywood, and scrapped sheet metal, but it was aesthetic in its lay out and functional in design. He had garden beds, and a chicken roost, and we ate fresh eggs for breakfast and fresh salads for dinner. Dev was an educator, and by his words he had worked with every kind of student. He had taught at the college level, and the high school level, he ran programs for home-school students, taught students with special needs, and worked with kids in juvenile detention. He’d had many conversations with students across the country about what it was they actually wanted to learn. Dev was also highly educated. He had a Masters degree and a PhD, and he had worked with top academics throughout the states. When we met him, he was transitioning his work to offer courses to students who were seeking a different way to learn.

“I’ve spent a lot of time working with kids who didn’t go to school at all, who were homeschooled, or were unschooled,” Dev told me, “Their way of getting an education was do whatever feels important or compelling at the moment and trust that those meaningful moments will lead to a meaningful future.”

In the morning, the sunrise burst over the mountains – dancing on the beads of dew that had fallen on the high grass along the road. In the evening, the sunset turned the mountains into a deep purple as it sank below the desert horizon. It’s strange to admit, that on a trip where I was interviewing people about the financial trap of debt, there was a real sense of freedom in my life, like I was directing the way forward as I had never done before. I had been from New York through Appalachia, and Chicago down to New Orleans. I would go through a cattle ranch in Montana, the red rocks of Utah, and a philosopher’s farm in Sonoma. I met fisherman, coal miners, teachers, and biologists, and I got to ask all of these people for advice. What I was told was that this was the age to explore, that these experiences would teach me how to live with intent. But what became obvious, was how lucky I was – how few people were getting to follow the advice that I heard. For every person that told me to “follow my passion”, there was another person that seemed to have lost that opportunity.

This made me think back to my interview with Jeff Franklin, who had said that an education is meant to liberate. I wanted to believe that, so as California got closer, my trip almost over, I began to think about how I could hang on to that feeling of freedom, about what could change so people had access to an education that gave them more of a voice. That’s how I found Dev, because I wanted to know if there could be another way.

As I talked to Dev about how he educates students, it became clear that he teaches by listening. He asks his students what it is that they want to know, and then he finds ways to empower them to figure it out. The answers he receives touch on ideas that are often overlooked in traditional learning.

“If you pay attention to what these young kids really want to learn,” Dev told me, “If you really listen to them, the most important question is how do I lead my life?”

“How do I lead my life?” I can’t remember being asked that in school. I had good teachers, but much of school was still a place where I learned to do what other people told me I should. “You get the idea,” Dev said, “that learning is something that is someone’s else’s job to give to you. That your job is to just be measured, to try to please the teacher, to do what’s good enough”. That statement resonated with me, as it did with many of the people on my trip. There was a sense of dissatisfaction with education. People felt as if it stunted their voice.

Dev told me that the biggest fear that he hears, when trying to show students a different path through the programs that he offers, is that if they don’t follow the traditional steps they won’t get in to college. He said they are pretty much always wrong – that when a student steps out of the system they grow into a person that colleges will fight for. In fact, he said, they often grow into people that don’t need college at all. “But that’s the fear,” Dev told me, “Because that’s what most people have seen. Their parents went to college – everyone they know, that’s what it took. So it’s hard to believe that a different way is possible.”

Later, before I left Paonia to move on with my trip, Dev asked me,

“What does it mean to be excellent in being free.” He smiled, “Kids get excited about that, and it leads to real valuable and tangible skills”.

That’s what Dev was trying to teach to his students. To show them they had the power to create meaning for themselves. It wasn’t that he thought we didn’t need schools. Rather it was that educators needed to learn how to ask better questions.

I met Sam keen, an 80-year-old author and philosopher, on a warm April day at his farm in Sonoma County, California.

He lives off a long dirt road, and in his backyard is a trapeze, which he uses to teach abused women and abandoned youth the ability to trust again. “You go up there and if you can’t deal with fear and risk, you can’t do it”, he said. “That’s what we teach with the trapeze. First time’s for fear, second time’s for fun”.

Sam told me that since the beginning our country bought into two narratives’ that were unique at the time. The first was the “Myth of progress” – the idea that progress was forever, that technology would insure we advance. The second was the “myth of the individual” – the idea that on our own we could stand strong, the sole agents in our growth. He believes that these two narratives led us to assign a “mythological” value to money. He says we’ve become economic beings, defined by our wealth. In doing so, we’ve assigned money the ability to build us or to ruin us. Yet it’s important to remember that the systems we enslave ourselves to are constructs of our own creation.

I was introduced to Sam’s work through a class I took in college where we watched one of his films. When I started this trip, I looked him up and I found some of his writing. I was drawn to a list of what he called “the great questions”. Two which stuck out, were, “Who has defined success and happiness for me?”, and “Who gave me the map I have followed so far?”. As I talked to people in debt, it seemed they were asking variations on this question. They thought by getting an education they were on the path to future success

“The willingness of people to go into this kind of debt is predicated on the idea that what they are going to learn is going to be a compensation for that debt. And as you say, so often, it is not,” Sam told me. “Debt is a mortgage. You’re mortgaging your future. It doesn't mean you can't rise above the burden of that debt, it just means that you have hostages to fortune.”

He continued, “if you put this question first, how are you going to utilize your gifts, you may find out that the traditional way of pursuing that question is not relevant at all.”

When I asked Sam about alternatives to college, he said we learn so much from life that we don’t count as our education. “That’s exactly what you’re doing right now,” he told me. “Your ass is hanging over a cliff too. This might not even make it into a film festival. You’re taking a big risk with your life and what you want to do.” He paused and smiled, “Your education was just 101, you’re in 202 now.”

I asked him later, whether it was a just a privilege of the few to be able to ask these questions, or to step out from the system. “Is it a privilege?” he paused, “Yes. But I think that those of us who have the privilege have an obligation to those who don't, to try to spread that privilege.” He went on, “the primitive economy was based around the idea of gift. It was what you gave that created your prestige. I think it is still a fundamentally good idea.”

Maybe that is what we’re missing most. Reform could start there, in finding ways to spread this privilege. How could we educate people so we’re teaching them what they need to know, so we’re getting them closer to the freedom we preach?

Chapter 13

DRIVER OUT

Chapter 13

DRIVER OUT

Last February I got an email from Tim.

“How’s the progress going?”, it read, “If you’re wondering about me; Same shit, different day”.

He went on to say that he was getting a Masters in secondary education. He was paying out of pocket as he went. “I don't need to add to the debt I already have when the interest alone is doing that”, he told me. His goal was to teach acting and filmmaking, to stay close to the things that he loved. He was also coming up on his 10th year of loan payments. He hoped to work out a settlement deal with Sallie Mae – to pay them his principal balance plus interest on their standard 10-year repayment plan. This would come to about $58,000, minus the amount he already paid. He thinks if he could find a job with a salary of $30,000 a year, he could put everything towards his loans, and hit that number. I told him it sounded reasonable, but I would be surprised if they worked with him.

I had sent Tim a trailer for this project. There was a sound bite of his that I wanted him to see.

“I like it!” he wrote, “but I don't want to come across as a lazy apathetic student debt holder. Most people generalize us (me, at least) because we got an arts degree. "How irresponsible!" When I was 18, college was the next step in life. I knew I had a specific skill set, and I wasn't interested in science, technology, engineering, or math. I wasn't aware of a debilitating debt in my future. No one truly warns you about the repercussions. Instead, they say everybody gets loans – as if it's okay to get into massive amounts of debt. They should be telling you it's not!”.

Out of the hundreds of people I met on this trip, only two would I classify as apathetic student debt holders. They were anarchists who worked on a weed farm and were refusing to pay. Everyone else was a hard working individual, just Americans who wanted a good enough job to get by. I hesitate to write about their resiliency. I don’t want it to be skewed to mean they’re doing fine. But the people I met were resolute in their realities, and they did an incredible amount of work to stay solvent. I was often inspired by the hope they held on to.

With no financial education, Tim was asked to sign for a loan that had a 13.2% compounding interest rate. While in forbearance programs, his interest capitalized, and he owes over $90,000 on an original balance of $32,215. When I met him he was paying Sallie Mae $700 a month in interest only. As I started this trip, I wondered why students in debt weren’t making much noise about this crisis. What I found – what Tim shows – is that this system can bury people too deep to be heard. The people I spoke with stayed quiet because they were too busy to get loud. When you are only focused on survival, it is really hard to change things.

People ask me what the solutions are. The loan system is intertwined with many things in this country. It’s tied to Wall Street, corporate greed, and congressional gridlock, so fixing it seems extremely difficult. There are little reforms though that could have an impact. The Federal government could stop financing for-profit colleges to prey on veterans with G.I. Bill money. Student loans from private borrowers could be regulated, such that predatory interest rates aren’t allowed. The federal government could pass legislation to allow students to declare their debt in bankruptcy, giving the worst off a fresh start. The government could refinance student’s debt at a lower interest rate. They lend to the banks at a rate of less than 1%. Perhaps students could get a similar deal. Both federal and state governments could increase their funding of higher education, bringing prices down. Universities could look at their cost structure, and find ways to offer cheaper courses, or get creative about how students pay for their time. High school counselors could be educated about the debt crisis, and there could be a mandatory financial literacy course that prepares students to make better decisions about college loan debt. Colleges could be asked to provide this course as well, and Sallie Mae could be forced to walk students through these loan programs in a detailed discussion of how they work.

These reforms would be fairly simple if congress could agree that action is needed. But private loan companies and for-profit colleges have spent millions lobbying congress to buy their influence. So although those reforms would help, it feels like what we really need is an awakening to the morality of these issues. It has been shown that a society does better when the majority of people are able to contribute. It’s important to consider the implications of a generation that is buried under debt. It has been well documented that student loan borrowers are less likely to buy a house, or a car, or start a family. That has a real economic impact that ripples through society. But I think there’s also an impact, a slow decline that happens, when people are left to the margins to fend for themselves. Middle class America, through debt, job loss, and wage cutting – has seen a slow unraveling – an erosion that leaves people on either side but not in the middle. There’s a cost associated to this. People forget that without a center, things become hollow.